Working Memory Difficulties

Here we aim to break down working memory and how you can support students with working memory difficulties for educators and clinicians alike.

Working memory

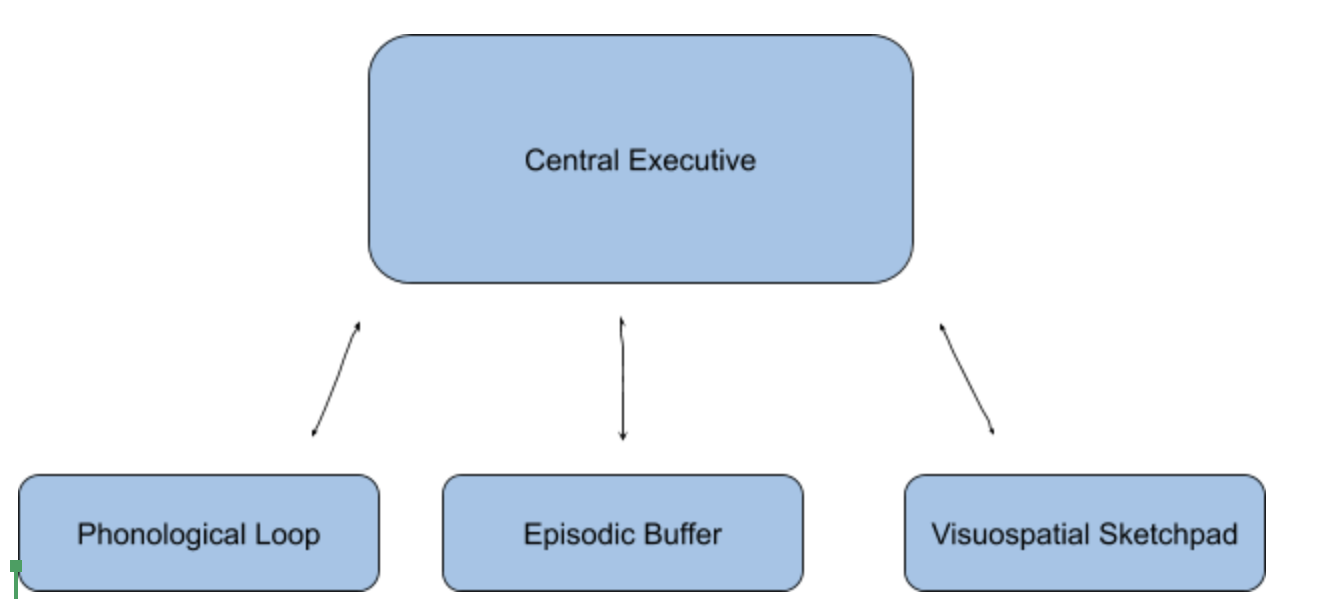

Working memory is widely accepted as a complex system with different sub-systems for different types of information. Following Baddeley & Hitch’s (1974) model it can be broken up into the following parts:

- Central Executive: In charge of the whole system and directs information to the correct subsystem while monitoring and coordinating them.

- Visuospatial Sketchpad: stores and processing visual/spatial information

- Phonological Loop: stores and processing spoken and written information.

- The Episodic Buffer: links to long term memory.

Working memory is important for any task that requires you to ‘hold’ onto information both for processing and for storage (Gathercole & Alloway, 2006). It also has a symbiotic relationship with speech and language (Archibald, 2017) and the two domains influence each other. Working memory influences academic progress and students with working memory difficulties are more likely to struggle within the classroom.

Working memory difficulties may be identified in a student who has:

- Verbal language difficulties: limited vocabulary, poor grammar.

- Written language difficulties: difficulties learning to read, decoding, understanding written text.

- Poor academic attainment in comparison to their peers.

- Difficulty following instructions.

- Difficulty remembering immediate things e.g. somebody’s name, the task they have been given.

- Difficulty following through and completing tasks.

- Highly distractible

Assessment

Working memory can be assessed through forward and backward digit span assessments which are found in numerous test batteries. Specific standardised assessments such as The Working Memory Test Battery for Children (ages 4 to 15 years) and The Automated Working Memory Assessment (ages 4-22) are also common. When assessing working memory be aware that when using linguistic information these tests are sensitive to language and literacy deficits (Alloway & Gathercole, 2005). However using linguistic information can be useful to assess phonological short term memory.

How to support children with working memory difficulties in the classroom setting

Singer & Bashir (2018) presented a framework to guide working memory interventions as follows:

- Working Memory Cannot Be Directly Manipulated to Improve Contextualized Language Processing. The use of ‘brain training’ or computer based training programmes have little evidence that their outcomes generalise to language and academic tasks that are untrained (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013).

- Increasing language ability frees up resources in working memory: in turn, this functionally improves working memory capacity. By providing intervention that aims to increase the awareness of and automaticity of language, this can ‘free up’ resources in working memory, thus reducing the effort needed to process language and this effort can be applied to different things.

- Storage and processing of verbal information can be supported through visuals. Using visuals to support verbal working memory so that language is concrete and does not move has been empirically shown to support verbal working memory. Not only that, but Gill, Klecan-Aker, Roberts, & Fredenburg (2003) found that using visuals alongside rehearsal strategies had better long term outcomes than rehearsal strategies alone.

- Verbal Working Memory can be supported through external language factors. Monitoring rate of speech, emphasis, sentence length and complexity as speakers, we can make adjustments to better support those with working memory difficulties.

- Professionals should collaborate to support those with working memory difficulties in the classroom. Supporting these students should be a multi-disciplinary effort and should take into account the uniqueness of each student.

Examples of Visual Aids

- Advanced Organisers

Advanced organisers show the key concepts and ideas prior to learning i.e. at the beginning of a lesson. They may show previous content covered to prepare and revise the student for the lesson.

- Graphic Organisers

Graphic organisers show key concepts and their relationships. They can be constructed by hand, filled out by student or teacher/therapist, completed before teaching, during or after instruction. However, there is still much more to learn about which method of use is superior (Singer & Bashir, 2018).

There are many different formats a graphic organiser may take: flow diagram, venn diagram, cause and effect. Bromley, Irwin-De Vitis, & Modlo (1995) discuss 9 graphic organiser patterns which we have illustrated in our gallery below.

Summary

Working memory difficulties will have an impact on language and academic functioning. There is little that can be done to increase working memory capacity directly (Melby-Lervåg and Hulme, 2013) , but there are interventions and strategies (such as using visual aids, compensating within the classroom, focus is on the automaticity of specific skills which in turn free up working memory, teaching the student strategies e.g rehearsal, asking for help.) that can have a huge impact students to access and learn within the classroom.

Resources

Working Memory: A guide for teachers (Gathercole & Alloway): https://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/WM-classroom-guide.pdf

Making Sense of Interventions for Children with Developmental Disorders: A Guide for Parents and Professionals (Book): https://www.jr-press.co.uk/making-sense-of-interventions-for-childrens-developmental-disorders.html

References

Archibald, L. M. (2017). Working memory and language learning: A review. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 33(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659016654206

Alloway, Tracy & Gathercole, Susan. (2005). The role of sentence recall in reading and language skills of children with learning difficulties. Learning and Individual Differences. 15. 271-282. 10.1016/j.lindif.2005.05.001.

Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8, 47–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60452-1

Bromley, K., Irwin-De Vitis, L., and Modlo, M. (1995). Graphic Organizers: Visual Strategies for Active Learning. New York, Scholastic Professional Books.

Gathercole, S. E., & Alloway, T. P. (2006). Practitioner review: Short-term and working memory impairments in neurodevelopmental disorders: Diagnosis and remedial support. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 47(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01446.x

Gill, C., Klecan-Aker, J., Roberts, T., & Fredenburg, K. (2003). Following directions: Rehearsal and visualization strategies for children with specific language impairment. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 19(1), 85–103.

Melby-Lervåg, M., & Hulme, C. (2013). Is working memory training effective? A meta-analytic review. Developmental Psychology, 49(2), 270–291.

Singer, B. & Bashir, A. (2018). Wait…What??? Guiding Intervention Principles for Students With Verbal Working Memory Limitations. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools. 49. 449. 10.1044/2018_LSHSS-17-0101.